Fast parallel sliding-window based binary diff

2020-10-21 @ 05:27 | Approx 11 minute readThe Problem

The issue I was facing was simple, I needed to diff a binary file with itself. I am working on a project called Nox which is a documentation and software project for the Agilent N2X protocol analyzer chassis and the PCI-Express analyzer modules that it can use.

The whole Nox project came about because the software to use the analyzers is old and crusty, and really only runs on Windows XP, 7 if you put some effort in. During picking apart the packet captures to understand the protocol that is used between the hardware and software, we ran into these very large configuration blocks, they control who knows what options so we needed to figure that out.

Seeing as the block are very large (read 64KiB), and we want to see what states change within the configuration block when flipping switches and changing settings. So the trivial way to do this is to capture one, then just diff every capture to find out how they differ. It's fairly straightforward, but initial investigation lead me to the conclusion that these configuration data frames are composed of many 32-Byte chunks. Initially the idea to diff each chunk to see if all the settings are identical within the initial large block was needed.

The issue with this is that if you need to diff every 32-byte chunk with every other 32-byte chunk, you get a lot of comparisons, around 4.194.304 for just 2048 blocks, which makes sense as that's \(n^2\).

The naive way of doing this will take ages to do all of those comparisons, so I had to find a faster way.

Fast binary differencing

Now that we have a small set of differences to actually compute, we need to speed up how the difference is actually computed.

The "Trivial" Way

The trivial way to do this is that when given two windows A and B, just loop over each byte in the window and check if they are the same. Below is some C++ of what that would look like.

for (std::size_t index{}; index < window_size; ++index) {

if (A[index] != B[index]) return true;

}

return false;

And wouldn't know know it, this can be the fastest way to do it, the compiler is smart enough to know how to vectorize this code and make it super speedy.

But for the sake of argument, let's go over how to also do it in AVX2, as it's a good exorcise in bit arithmetic.

The "Optimized" Way

The reason why we are using AVX2 is due to the window size that has been picked, 32-bytes. It turns out,the AVX2 registers are all 256-bits wide, or 32-bytes. So this lets us load a whole window into a single register.

The trick with the AVX2 based diff method relies on how the _mm256_cmpgt_epi8/vpcmpgtb intrinsic / instruction works, along with _mm256_movemask_epi8/vpmovmskb and how XOR works.

For a simplified example I will demonstrate how the math works using 4 bytes, rather than all 32, but the result is the same.

The first step is to XOR each window together, this will cause all non-differing bits to be set to 0, leaving only bytes that differ to be non-zero.

0x7F 0x45 0x4C 0x46

XOR 0x7F 0x43 0x4F 0x57

-------------------

0x00 0x06 0x03 0x11

Now, you take the resulting bytes, and use _mm256_cmpgt_epi8/vpcmpgtb to compare it with a fixed zero vector. The way that instruction works is that if the comparison is false, then the byte is zeroed out, and if it is true, then byte is filled.

0x00 0x06 0x03 0x11

CGT 0x00 0x00 0x00 0x00

-------------------

0x00 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF

Now we have a vector filled with which bytes differ and which don't distinguished by if they are filled or zeroed, and this has the very nice side effect of allowing us to use _mm256_movemask_epi8/vpmovmskb to create a bitmask of which bytes in the window are different, as well as providing a value that is larger than zero if the windows differ at all.

What it does, is take the sign bit of each packed 8-bit integer in the vector and pack the sign bits into a single 32-bit mask. Like follows:

MM 0x00 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF

-------------------

0b0 0b1 0b1 0b1

0x07

With that, we can see that the hamming weight (or popcount if you want, same thing) is 3, meaning that 3 out of our 4 bytes were different, and the bit at each position is the byte in the window which is different.

The following C++ snippet is the full implementation of what we just described which then returns a std::bitset<32> if there are differences.

std::optional<std::bitset<32>> avx2_diff(const uint8_t* win_a, const uint8_t* win_b) {

/* Allocate a static empty vector */

static const __m256i zero{_mm256_setr_epi8(

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00,

0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00

)};

/* Load the windows into their own registers */

const __m256i window_a{_mm256_stream_load_si256(reinterpret_cast<__m256i const*>(win_a))};

const __m256i window_b{_mm256_stream_load_si256(reinterpret_cast<__m256i const*>(win_b))};

/* Actually do the diff */

const __m256i diff_mask{_mm256_xor_si256(window_a, window_b)};

const __m256i res{_mm256_cmpgt_epi8(diff_mask, zero)};

/* Extract the result */

const std::bitset<32> diff{uint32_t(_mm256_movemask_epi8(res))};

/* If we have any differences return them otherwise don't bother. */

return (diff.any()) ? std::make_optional(diff) : std::nullopt;

}

As mentioned in the section above, this is actually slower than the trivial loop implementation, modern compilers pull no punches when doing loop optimization. This hits a point of AVX2 where there is a high-cost to pipeline warm-up, so if you can't keep the pipeline saturated it'll stall and waste cycles waiting for data. And the compiler can do this way better than a human can.

The Sliding Windows

Now that we have a method for differencing, we need to actually apply it to the file. This for the most part is easy, you just mmap(3) the file into memory with it's size set to include any needed padding.

This gives us a single contiguous address space in which we can do the comparisons from. The address of each window is simply the base address of the mmap(2) plus the window ID multiplied by the window size. So window 0 will be at the base address plus +0 and window 100 will be at +3200.

With that sorted, we can then figure out what all the windows are.

Computing Windows

The core concept is that this is a sliding-window based differencing engine, as such the window is a fixed size, in this case 32-bytes. Before we can actually do any differences, we need to figure out how many windows there are.

This is done fairly easily, assuming the window size is \(s\), the number of windows is \(\frac{F}{s}\) where \(F\) is the size of the file padded to the nearest whole window size.

Computing \(F\) is easy, first, take the modulo of the file size \(f\) and the window size \(s\), that computes the number of padding bytes needed to the nearest full window, which may also be \(s\) itself \(p = f \bmod s\). Then if \(p\) is the same size as \(s\) you just divide the two, otherwise add the padding to the file size then divide. $$n = \left\{ \begin{array}{lr} p = s & : \frac{f}{s}\\ p \ne s & : \frac{f + p}{s} \end{array} \right.$$

The following C++ code does the same as above

constexpr std::size_t window_size = 32;

const auto filesize = fs::file_size(file);

const std::size_t padding = window_size - (filesize % window_size);

const auto window_count = ((padding != window_size) ? (filesize + padding) : filesize) / window_size;

Difference De-duplication

The first challenge is to see if we can de-duplicate the number of comparisons, and thankfully to set theory we can! (Who thought that phrase would ever be said?)

We know the total number of initial window comparisons to be \(n^2\). However, we can take advantage of the fact that a large diff matrix like this can be considered as two sets. And therefore we can use fact that the symmetric difference of two sets are associative \( A \triangle B = B \triangle A\) just like a diff would be, as well as the fact that a set with it's own symmetric difference is an empty set, \( A \triangle A = \varnothing\). So we can use this fact to reduce the number of comparisons from \(n^2\) to \(\frac{(n^2)-n}{2}\). This reduces the number from 4.194.304 to just 2.096.128. That cuts the time to actually do all the comparisons in half, so now an operation that would have taken 30 minutes only takes 15 minutes.

Now this may sound complicated to implement, but practically it's actually really simple if you don't care how slow the de-duplication process takes, as seen in the snippet below.

/* Remove all the associative and self compares */

for (size_t row{}; row < window_count; row++) {

for (size_t col{}; col < row + 1; col++) {

window_matrix[row][col] = false;

}

}

Now once the de-duplication has been done, we now have a huge list of window comparisons that are all fully unique. And from just the window ID, we can compute the offset of the window into the file we need to go for the data. So all that is left is to the actual comparisons

Bringing It All Together

The final step is to actually do the comparisons, we have a full list of the things to be done, and a fast way to do them, so the only thing left to do is actually get it done.

Now there are two possible solutions one can thing of for this, the first is to loop over each comparison that needs to be done in serial, the other being to divide all the comparisons into buckets and then give each bucket to a thread to chew on.

Either way you decided to do it, at this point all that needs to be done is to compute the window address, diff the windows, and collect the results.

Closing Thoughts And Lessons Learned

At first glance the threaded option may seem better, I mean when doing lots of things in parallel then it gets done faster, right? Well, that can be the case, but there are also things that benefit from not being parallel, as funny as that sounds.

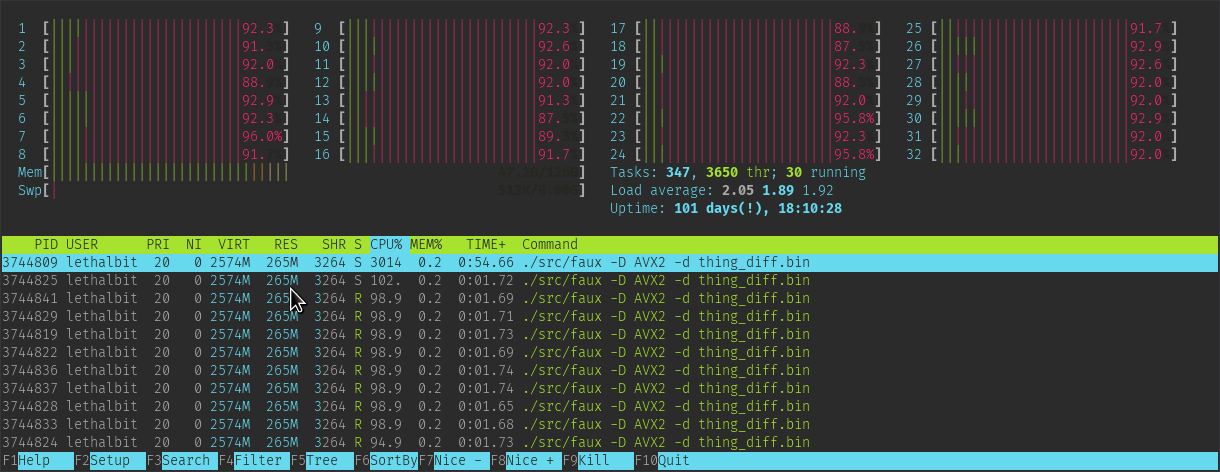

One such case is the whole point of this article, It's actually slower to run in parallel, even on 32 threads than it is to run serial. And that stacks on top of the fact the AVX2 implementation is actually slower than the trivial loop implementation.

Below are two runs with the AVX2 method, the first being threaded the second being serial.

Threaded Run:

real 0m3.686s

user 0m5.040s

sys 1m1.155s

Serial Run:

real 0m1.884s

user 0m0.727s

sys 0m0.519s

These next two are using the generic loop difference method, the first being threaded and the second being serial.

Threaded Run:

real 0m3.639s

user 0m5.199s

sys 1m0.405s

Serial Run:

real 0m1.738s

user 0m0.636s

sys 0m0.458s

I think this comes down to pipelining and how well the compiler can optimize for loops and memory access, but I'm not an optimization expert and I've only done a small trivial look into this.

Either way while I feel it may have been a total waste of time, I still learned a lot, and I hope that you did as well.

The project this article is based on is on my Github under lethalbit/faux and it's licensed under the BSD 3 Clause, so if you want to take it and make it better, or just look at the practical implementation of whats been written about above by all means do.